(This is the 8th post in a series that started here)

I thought I’d take closer look at the split data for the sub-2:20 runners, since I never get to see them while we’re all on the course.

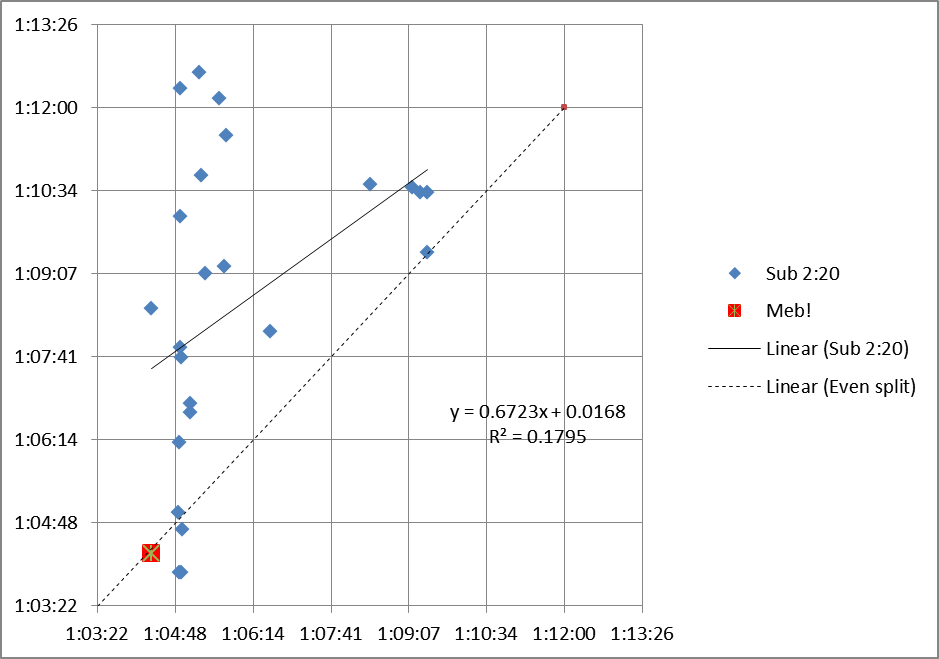

In my last post, I pointed out that on average, the faster runners tend toward negative splits more than the bulk of the field. But a close look at the fastest group reveals a lot of positive splits:

There’s a simple reason for this: the runners up front aren’t just competing against the clock for a fast time. They’re also competing against each other to win the race.

A relatively large number of runners are capable of sticking with the lead pack through the first half of a marathon. The very fastest runners hold the pace (or go even faster) all the way to the finish line. The remaining runners slow down and get dropped along the way. Those runners are represented by the vertical column of data points lined up above the winners.

In the case of Boston 2014, the lead pack went through the first half in about 1:05. In the second half, as most of the pack dropped off one by one, three runners were able to hold on through the Newton Hills and make it to the finish at a pace as fast or faster than their first half pace.

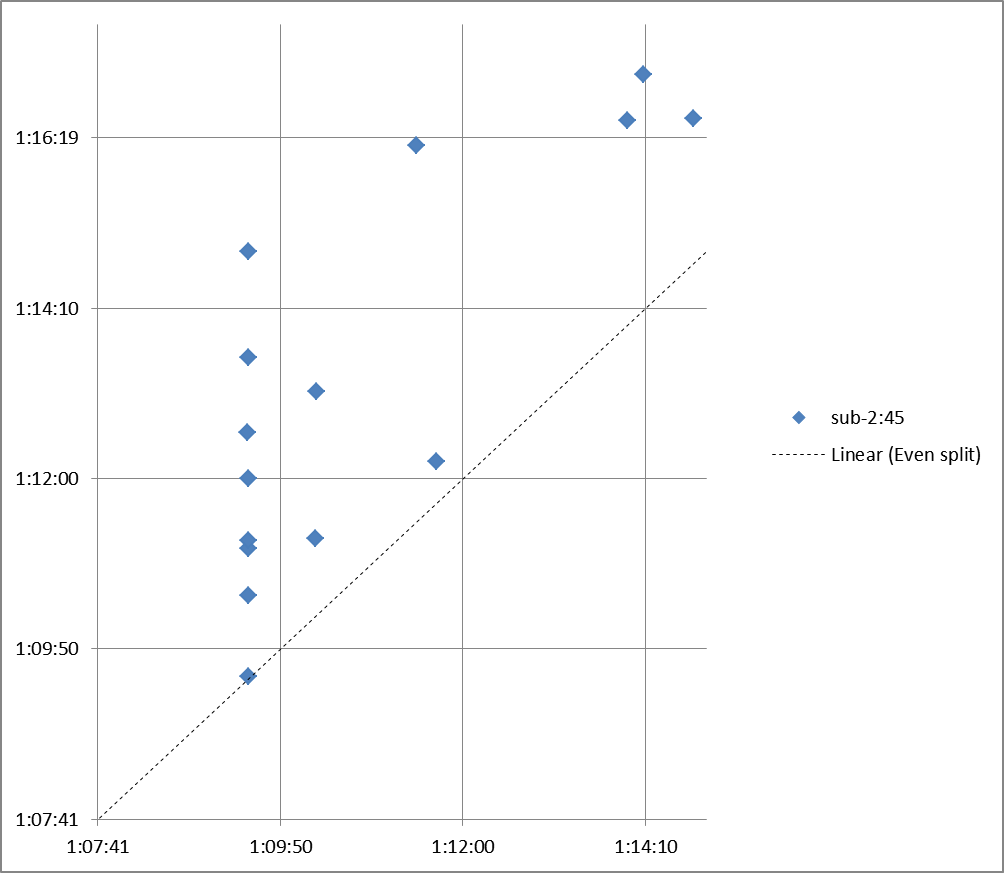

You can see the same effect in among the women’s leaders:

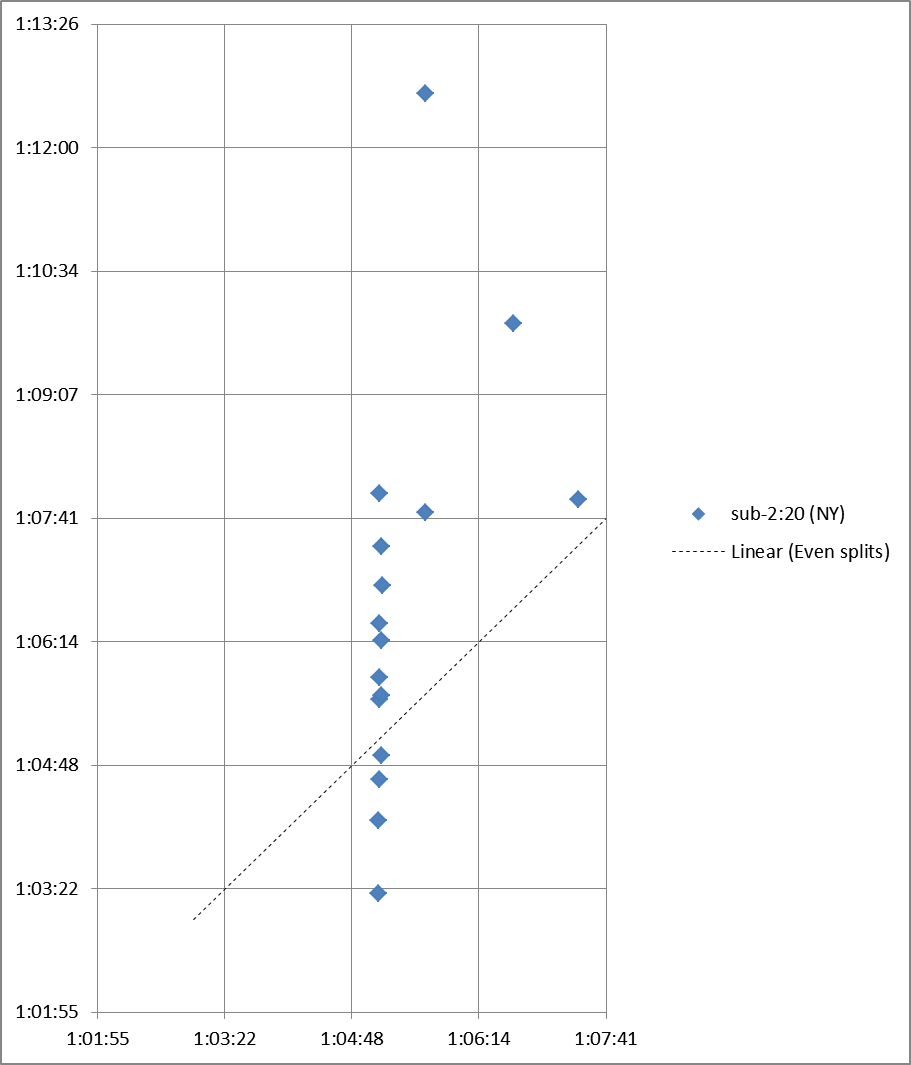

at the 2013 New York Marathon:

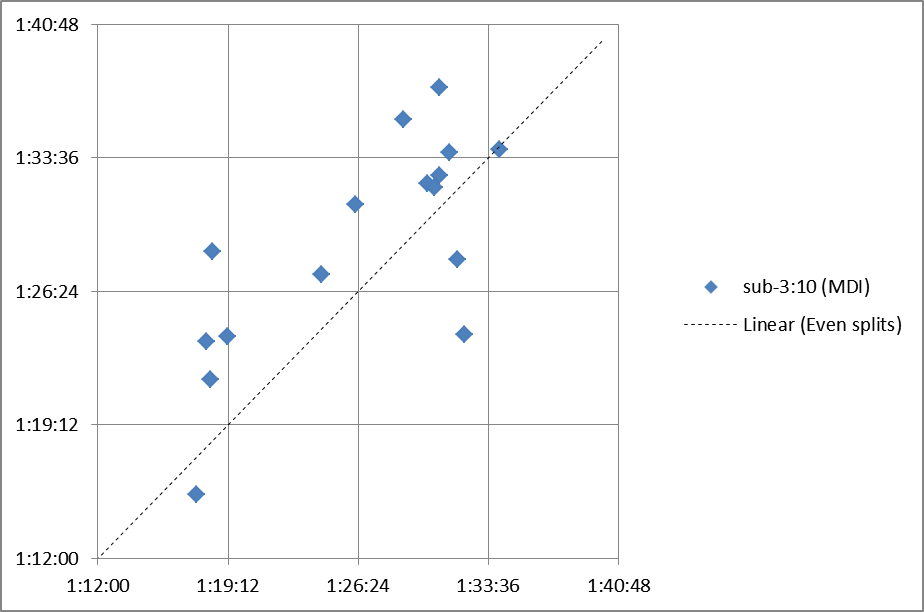

and even at smaller races with less competitive fields, like MDI 2013:

Now go back and take another look at the men’s chart from Boston 2014. What’s unique about it?

Only at Boston did one runner (Meb!) dare to go out ahead of the lead pack. Though he didn’t run the fastest second half split, he did run a negative split, and more importantly, he held on to win.

More to come in my next post…